FRANCES FARMER: SHEDDING LIGHT ON SHADOWLAND

FRANCES FARMER: SHEDDING LIGHT ON SHADOWLAND

The Truth About Frances Farmer

By Jeffrey Kauffman, © 1999, 2004, 2013. All rights reserved.

Journalist and researcher Jeffrey Kauffman has spent decades unraveling the Frances Farmer story and is the first person to obtain access to pertinent medical and court records which clarify many aspects of Farmer’s history while at the same time completely dispelling several commonly held beliefs about her. His research has been utilized as source material for a number of international television and radio broadcasts (including A&E and NPR), as well as innumerable national and regional print media reports and features. This article summarizes that research.

A Note About Sources from Jeffrey Kauffman: All specific published sources are cited within the body of this article. Other information in this article came from personal correspondence and interviews with a number of people who either knew or worked with Frances during her lifetime. The late Edith Farmer Elliot (Frances’ sister) and I engaged in both correspondence and phone conversations over the course of several months in the mid-1980’s. I met Frances’ nephew David online in the early 1990’s and we have continued to enjoy a friendship ever since. David provided tape recordings of his family discussing the errors in Shadowland. David, an attorney, also helped find the Arnold v. Brooksfilm lawsuit documents, which are available (with the complete text of the Judge’s decision and commentary which are excerpted below) to those with an account on LexisNexis.com and which are also available via Google Books. Western State Hospital archives are available to authorized researchers through Washington State. Jack Randall Earles and Patrick Agan (The Decline and Fall of the Love Goddesses) provided tapes of WFBM employees and Lois Kibbee discussing Frances. Information about Dr. Charles Jones came from his daughter and co-workers. Freeman biographer Jack El-Hai contacted me many years ago when he began investigating Freeman, and he relayed information about Freeman’s personal patient records (you will note I am thanked in the acknowledgements of Jack’s excellent book, The Lobotomist). Frances’ favorite director from her Indianapolis years, the late Dr. Joseph Stockdale, also provided information about her years in Indiana, her theater work there, and her general demeanor during these years. All sources utilized in this article remain in the Farmer Archive I manage and will be made available to any authorized researchers upon request. Individuals with questions about specific sources are encouraged to contact me.

INTRODUCTION

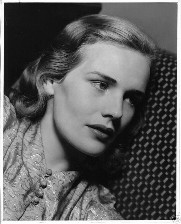

Frances Farmer died in 1970, after having lived a tumultuous life which saw her make national headlines in both high school (for her essay God Dies) and college (for her trip to Russia); become acclaimed by Cecil B. de Mille as the “screen’s outstanding find of 1936” and by Howard Hawks as “the greatest actress I ever worked with”; join the Group Theatre, one of the most important, socially conscious and artistically groundbreaking troupes in U.S. history; and suffer a harrowing, ongoing struggle with mental illness, which kept her in various sanitariums and hospitals from 1943-1950. In 1972, her purported autobiography Will There Really Be a Morning? was published to great critical acclaim.

The story might have ended there, but in 1978 Seattle film critic William Arnold published his account of Farmer’s life, entitled Shadowland. Arnold claimed to have uncovered previously undisclosed information that Farmer had suffered a transorbital lobotomy at the hands of Dr. Walter Freeman, the man who, with James Watts, had introduced the prefrontal lobotomy to the United States, and who had later “refined” his technique to avoid drilling through the skull, instead resorting to inserting an icepick like device through the eye socket up into the brain to sever the frontal lobes. Arnold’s disturbing account, the first time ever anyone had made the lobotomy assertion about Farmer, became the basis for the 1982 feature film Frances starring Jessica Lange. Many people, myself included, were introduced to Frances Farmer’s story through either Arnold’s book or the film, and believed (as I did for many years) that her story was accurately represented by these works. This, unfortunately, could not be further from the truth.

As family, friends and co-workers have stated, Frances no doubt exhibited strong neurotic, if not outright psychotic, tendencies during her troubled years (and even later), and continued to suffer from alcoholism for most of her post-institution life. She was, however, remarkably successful after her release from Western State Hospital and crafted a comfortable life for herself in Indianapolis from 1958 until her death. While she was obviously deeply scarred by her years of hospitalization, a lot of what the general public believes happened to Frances (including but not limited to the lobotomy) never actually occurred.

Like many interested in Frances’ story, I long thought Shadowland was the definitive account of Frances Farmer’s life. However, as I did extensive research through the years, I slowly began to notice mistakes and discrepancies in William Arnold’s account, ultimately leading me to doubt a great deal of what he wrote. It made me begin to wonder whether, for whatever reason, Mr. Arnold had an agenda in writing Shadowland, including but not limited to his sensational allegation that Frances Farmer was lobotomized. While Mr. Arnold is to be commended for bringing the horrors of the Freeman transorbital lobotomy procedure to the modern masses (it was quite a well-known procedure in its day, as will be shown), his major hypothesis of a ‘vast right wing conspiracy’ leading to a lobotomy is simply not supported by any facts, certainly not in his book, which steadfastly avoids citing sources while at the same time repeatedly making unsubstantiated claims. As will be discussed below, Frances’ sister was convinced Arnold’s account was a deliberate misrepresentation, part of a Scientology effort to reveal the supposed “horrors” of psychiatry.

Indeed, archival records (heretofore unreported) show definitively that Frances Farmer was never operated on for any reason at Western State Hospital. When considering the veracity of Mr. Arnold’s book, be aware of the following errors contained in Shadowland, any of which could have been researched and corrected with a little effort, especially considering the fact that Mr. Arnold is based in Seattle, where most of Frances’ life is part of the public record. Though some of these errors may seem minor, they point up a general sloppiness in the journalistic research required for an authenticated biography. Of course, as will be discussed below, Mr. Arnold claimed (after Shadowland had been written and marketed as an authenticated biography) that his intent was never to write an actual biography of Frances Farmer and that his book was, in fact, “fictionalized.” Here are just some of the errors and misrepresentations found in Shadowland:

BIRTHYEAR

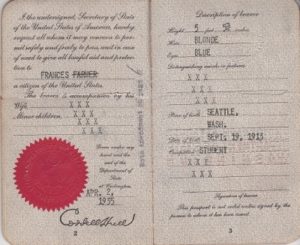

Frances’ student passport (used on her 1935 trip to Russia and Europe), clearly listing her birthyear as 1913.

Arnold states Frances was born September 19, 1914. As members of Frances’ family have confirmed and her birth certificate states, Frances was born in 1913. Additionally, Frances’ own passport (the one she used on her trip to Russia) clearly lists her birthyear as 1913. One assumes Frances would have filled out the paperwork for this document herself.

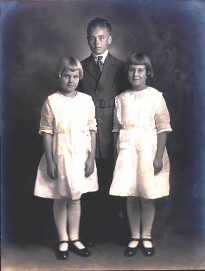

Frances (left) circa 1923 with siblings Wesley and Edith

“SHE WOULD NO LONGER RESIST AUTHORITY OR PROVOKE CONTROVERSY”

In his introduction, after making his completely unsubstantiated claim that Frances was lobotomized, Arnold makes the above statement about Frances’ supposed post-operative behavior. Frances’ years in Indianapolis (just one example) are filled with numerous anecdotes of her resisting authority, including an arrest for drunk driving and run-ins with station management at WFBM, and her rebellious, defiantly emotional attitude is well documented by friends and associates. There are both extant tv and radio interviews with Frances’ co-workers at WFBM attesting to Frances’ emotional outbursts, including a superb five part series which ran on WFBM circa 1982-83 when the feature film Frances was released. These first-hand reports of her behavior are in direct contradiction to Arnold’s assertions.

ALIEN CORN IN 1935

Throughout Shadowland, Arnold repeatedly makes timeline errors which are inexplicable, not only because the actual facts are easily obtainable, but even more so because he cites information (including pictures of newspapers, etc.) which is in direct contradiction to what he states. One of these errors lies in his statement that Frances starred in Alien Corn at the University of Washington in the fall of 1935. This is off by a year: Frances, receiving rave reviews, did this play in the fall of 1934. By the fall of 1935 she was signed to Paramount and living in L.A. This particular error is odd, as Arnold in the very next chapter goes into detail about the trip to Russia, correctly placing its genesis in the spring of 1935.

SHIP NAMED MANHATTAN

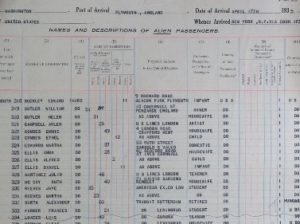

The actual manifest of the Washington, which took Frances across the Atlantic in 1935.

Arnold claims the ship Frances sailed on to Russia was the Manhattan. In separate books, Frances’ sister Edith and Patrick Agan both say the boat was the Washington. The image of the actual manifest (left) containing Frances’ name proves the ship was indeed named the Washington. Interestingly, Frances’ nephew David Farmer believes he traveled on the Washington with his father (Frances’ brother, Wes) and family when Wes was shipped from Bremerhaven to New York City by the Army in the early 1950’s.

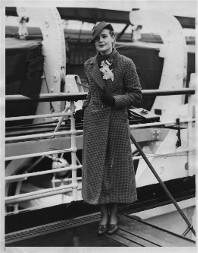

Frances preparing to board the Washington, which would start her on her journey to the USSR in 1935.

TRIP TO RUSSIA “BARELY MENTIONED” IN BIOGRAPHIES

Arnold alleges that her Voice of Action sponsored trip to Communist Russia is barely mentioned in any of the “meager” source material available to him at the time. Virtually every early fan magazine article on Frances, as well as the official biographies (including her Paramount Studios biography and the SAG-sponsored bio listings in the Motion Picture Almanacs of 1936-1944), clearly state that Frances’ journey to screen stardom started with a trip to Russia.

FRANCES 20 AT TIME OF RUSSIA TRIP

Due to his previous error on Frances’ birth year, Arnold states that Frances was 20 on her trip to Russia. This should have been a major red flag to Arnold as he was writing, as the only reason that Frances’ mother Lillian was unable to prevent Frances from taking the trip was that Frances had already turned 21 and was a legal adult.

“POWERFUL MOVIE MOGULS KEPT (THE TRIP TO RUSSIA) SECRET”

Frances’ trip to Russia, including its Communist overtones, is recounted in complete detail (including her parents’ shocked response) in several fan magazine articles about Frances, including the February 1937 Photoplay and the May 8, 1937 Colliers.

Frances and Leif in their Laurel Canyon home in 1937.

MARRIAGE TO LEIF ERICKSON

Arnold has his timeline slightly wrong. Frances married Leif during the filming of Too Many Parents in February 1936. There are numerous press accounts and fan magazine articles verifying this, including a February 9, 1936 wire service report which appeared nationally and contains a great quote from Frances’ mother Lillian that she had “never heard” of Erickson.

ERICKSON REFUSES TO TALK TO ARNOLD

Arnold claims Erickson’s PR person told him that Erickson considered Frances’ problems a mystery and refused to comment. The implication is that Erickson had nothing to do with Frances after their separation. Not only did Erickson appear on Frances’ Indianapolis tv show, Frances’ nephew David Farmer has recounted that Erickson stayed in good touch with the Farmers throughout the decades after his divorce from Frances, checking up on Frances during her life, and continuing his relationship with Wes and Ruth Farmer (David’s parents) even after Frances’ death in 1970.

FRANCES REFUSES TO AUTOGRAPH COPIES OF COME AND GET IT

She autographed at least one, as it is in my personal collection!

“THERE IS NO EXISTING PRINT OF BORDER FLIGHT”

I discovered a print fairly easily in the (largely pre-internet) early 1990s.

LOTTA IN COME AND GET IT

Arnold states Virginia Bruce was originally signed to play this role. Authoritative biographies of Goldwyn and Hawks state that Goldwyn originally announced Miriam Hopkins (whom Hawks did not like) for the dual role. Hawks was therefore initially interested in casting Andrea Leeds (who eventually played Edward Arnold’s daughter), until he met with and screen tested Frances. Anne Shirley portrayed the dual role in the Lux Radio Theater broadcast of Come and Get It in 1937.

Frances relaxing between takes of Toast of New York.

“ALIENATED CO-WORKERS STATED THEY WOULD NEVER WORK WITH HER AGAIN”

Arnold provides no substantiation for this statement regarding the filming of Come and Get It. None of the articles and press accounts available suggests any such statements were made. In fact, Edward Arnold is quoted in Modern Screen during the making of Toast of New York (his second film in a row with her) that if Frances’ performance in Toast matched Come and Get It, he fully expected her to be a major star.

1937 MOVIES “ENORMOUS HITS”; FRANCES RECEIVED EXCELLENT REVIEWS

Toast of New York was actually a notorious flop. It was the most expensive movie made in 1937, and caused major financial problems for RKO due to its lackluster boxoffice. Frances’ reviews in all three of her 1937 movies were decidedly mixed. Modern Screen in December 1937 even states that after the pans she had received in Toast and Ebb Tide, Frances was chastened after becoming haughty with success after Come and Get It.

Widely used publicity photo of Frances in Golden Boy. This same pose was used as the basis for a gorgeous full color pastel illustration that ran in the Washington Post.

REVIEWERS SINGLE OUT FRANCES IN GOLDEN BOY

Arnold claims reviewers singled out Frances as the “finest thing” about Golden Boy. While most reviewers were in no major way critical of her (though some did indeed pillory her performance), several mentioned her obvious lack of experience and even her miscasting in the role (see Time’s review for an example). All reviewers were in unanimous agreement that the best thing about the play was Odets’ pungent dialogue. In fairness to Arnold (and Frances), her reviews in the national touring company of Golden Boy were rhapsodic (see next entry).

GOLDEN BOY NATIONAL TOUR

Arnold states Frances’ heart was not in the tour. Contrary to the reviews of her Broadway performance, which were mildly favorable at best, the reviews of the national tour of Golden Boy repeatedly mention Frances’ intelligence and depth of characterization.

QUIET CITY

Arnold glosses over this play, alleging only that it was an enormous failure and that it was the first major setback of Frances’ career. In actuality, it was never a full-fledged production at all. Rather, it was an experimental piece that ran for only two Sunday night performances during the spring of 1939, crammed into the Belasco Theater (where Golden Boy had run two years previously) where another Irwin Shaw play was already running during the week. The Group had wanted to utilize some of its off-duty actors in some short-run experimental pieces. If Quiet City had been better received than it was it may well have run longer than only two weeks; as it is, it is chiefly remembered for its elegiac Aaron Copland underscore, which he later reworked into a popular orchestral suite. Full details can be found in the autobiographies of Harold Clurman, Irwin Shaw and co-star Norman Lloyd, as well as Wendy Smith’s excellent account of the Group, Real Life Drama.

AFFAIR WITH ODETS

Arnold’s timeline is wrong. For details, see any of the excellent biographies on Odets, especially the one by Margaret Gibson. Frances herself hints at a different timeline for the affair in the May 4, 1958 American Weekly article she co-wrote, one in which he refers to Odets as “Mr. X”.

One of the few existing press photos from Frances’ brief involvement with The Fifth Column, here with Franchot Tone.

THE FIFTH COLUMN

Arnold alleges that The Fifth Column never opened on Broadway after Frances withdrew and Katherine Locke was hired to replace her. He also states that Frances’ reputation was irreparably damaged because she had “destroyed” the production. The Fifth Column opened on Broadway on March 6, 1940, and ran for a respectable, if not record-breaking, 87 performances, closing on May 18, 1940. It received favorable to rave reviews from all the NYC critics. Aside from trade papers like Variety, which covered the dispute with Equity that ensued when Frances left the production, Frances’ involvement in the play is not mentioned in any reviews or press coverage of the play.

1941-42 AND SON OF FURY

Arnold’s account of this time period is studded with errors, including his statement that Frances’ mother made a “brief” visit (she actually stayed almost three months). The most egregious error is his claim that Frances made Son of Fury in late 1942. Son of Fury was released in January 1942, so Arnold is obviously incorrect. Frances’ brief role was filmed in late fall 1941 (she was actually the third actress cast for the role, after an almost comedic series of events took out Maureen O’Hara and Cobina Wright, Jr.). What is most intriguing is the lack of information about what Frances did in the nine months of 1942 before her arrest; read Patrick Agan’s account in The Decline and Fall of the Love Goddesses for details. This is, in some ways, the most importantly neglected time period of Frances’ impending troubles.

1954 wire service photo of Frances with fiance Alfred Lobley, which ran with a nationally published interview with both of them.

“LAST PERSONAL INTERVIEW”

Arnold recounts Frances’ 1941 interview by the Seattle newspaperman Walter Rue and states “it was the last personal interview she would ever give.” Frances granted numerous personal interviews during her 1957-58 comeback period (some of which Arnold himself documents later in his book), and continued to be covered in both the Indianapolis and national press with great regularity throughout the run of her tv show, and even later with the launch of her decorating business and continuing personal appearances. There was also national press coverage, including interviews, of her marriage to Alfred Lobley in Seattle in 1954, as well as her infamous 1964 appearance on the Today Show.

Frances’ Santa Monica rental, where she lived for several years in the 40s. Next door to this house is the expansive Deco mansion that belonged to Delores Del Rio and Cedric Gibbons.

FRANCES’ DRUNK-DRIVING ARREST; DEL RIO HOME

Arnold makes three errors in his account of this event. He indicates Frances was on her way to a party for Deanna Durbin when she was arrested. Other accounts, including Frances’ own in a 1958 American Weekly three-part series she co-wrote about her troubles, contemporary news articles as well as an eyewitness account by Ruth Farmer (Frances’ sister-in-law), state unequivocally that Frances had actually been visiting her half-sister Rita (and had imbibed, by her own admission, a few beers) and was on her way back home when the arrest occurred. (To anyone who has studied Frances, the thought of her attending a party held by Deanna Durbin, who would have still been a minor in October 1942 and who according to several accounts was not even in Hollywood at that time, is highly unlikely). Arnold also states that Frances’ rented house belonged to Delores Del Rio and was in Malibu, and that she was passing through Santa Monica when she was arrested. Contemporary news accounts of her arrest state her address and prove that Frances rented a two-story Colonial home that was on the same street as the Del Rio home, but that she never lived in the Del Rio home. Additionally, both Frances’ home and the Del Rio home were in Santa Monica, and Frances was nearing her home when the arrest occurred. (There are numerous 2022, i.e., official Paramount PR photos of Frances, at this home as well as a Natural Gas ad campaign in the December 1941 Sunset Magazine featuring the home).

Only known publicity shot from Frances’ one day of filming on No Escape.

APPEARED IN 18 FILMS

Arnold, in recounting Frances’ emotional distress at having been overworked for years, states she had been in 18 feature films (among other credits), which is among many items he evidently culled from Will There Really Be a Morning?, a book he lambastes for its many errors. (See additional entry on this book below).

The notoriously cheap King Brothers used a brief shot of a troubled looking Frances in a montage in No Escape. (Photo courtesy of Jack Randall Earles)

By 1942, Frances had appeared in fourteen films. She would make her fifteenth, and final, film in 1958. (She may have done some minor master shots for the Mexican production Five Were Chosen before she was deported and she did complete one day of filming on No Escape in 1943 before her parole violation arrest. Aside from an approximately one-second shot used during a montage sequence in No Escape, she is not in either film).

FIVE WERE CHOSEN

In one of the more in-depth sections of his book, Arnold’s account is again studded with errors. He refers to the film Frances went to Mexico to shoot as Hostages, which evidently was a working title at some point, but which was never officially used. He states the film was unfinished, although it was in fact completed and released under the title Five Were Chosen. In one of the strangest episodes in Arnold’s book, he claims he “uncovered” the fact that Frances had simply “drunk the water,” so to speak, and had become seriously ill with turista, something Arnold states he, perhaps sympathetically, also came down with as he investigated in Mexico City. Edith Farmer Elliot goes into some detail in her book over Frances’ deportation, and chalks it up to a fight in a hotel. Though Edith’s memory seems almost frighteningly picayune throughout her book, in this particular instance she may have interpolated Frances’ January 1943 fracas in a Hollywood restaurant with this incident, which took place in December 1942. A fascinating first-hand eyewitness account is given by Ricardo Montalban (Five Were Chosen was one of his first films) in a long interview archived by the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Montalban, after stating how beautiful and talented Farmer was, states that she was suffering from mental problems and that one night a few days before filming began she roamed the halls of the hotel where the cast was staying, wearing no clothes and spraying people with a seltzer bottle. (You can view the video here. Montalban’s comments about Frances begin shortly after the 5:00 mark.) This incident is also tangentially referred to in a January 1943 Walter Winchell column where Winchell states she was deported for “raising a rumpus at the Ritz Hotel” in Mexico City.

BUSINESS MANAGER SUBLET MALIBU HOUSE

Arnold repeats his earlier error about the location of Frances’ rental home, but also states that Frances’ business manager had sublet the home and moved her personal items to the Knickerbocker Hotel. Tapes of Ruth Farmer clearly state it was Frances’ relatives, including Ruth herself, who moved Frances’ items, both because of financial reasons (Frances was running out of money) and concern over her increasingly erratic behavior. Edith Farmer Elliot also acknowledges in her book that it was her brother Wes and Wes’ wife Ruth who moved Frances’ items, and that Wes actually burned Frances’ in-progress autobiography to keep it from “falling into the wrong hands.” Edith seems to realize this sparked deep distrust of her family in Frances at a time Frances could least afford it.

A disheveled yet defiant Frances after her arrest in January 1943.

FRANCES’ ORIGINAL COMMITMENT: “NOT APPARENT FROM THE RECORD”

Arnold states that the facts surrounding Frances’ original commitment after her parole violation arrest are not clear. He states “weeks of research provided no explanation.” However, several contemporary news reports of the arrest and commitment clearly state that Frances’ sister-in-law, Ruth Farmer (Wesley’s wife and a deputy sheriff in LA county), was present at Frances’ hearing and felt psychiatric treatment would be preferable to jail. That is how a decision to commit was made and how Dr. Leonard became involved in Frances’ case (again in direct conflict with Arnold’s depiction of Leonard’s involvement). Frances’ brother Wesley actually signed the commitment order, not Frances’ mother Lillian. Arnold also attributes quotes (some altered by Arnold from the originals as reported) to Frances from a supposed conversation with Leonard which according to contemporary press accounts were made to the press and other spectators before Leonard was involved in the case.

UNSYMPATHETIC NEWS ACCOUNTS

Arnold claims that contemporary news accounts of the arrest and commitment were “callously unsympathetic.” In actuality, from the wire services to such magazines as Time and Newsweek, reporting on this chain of events was by and large balanced and extremely sympathetic, including the famous quote of Frances’ troubles having been caused by a broken heart. Follow-up articles written over the months following her arrest and commitment from industry papers like Variety to fan magazines were uniformly sympathetic.

PRIVATE SANITARIUM

Arnold states that information on Frances’ stay at a private sanitarium (the Kimball Sanitarium, no longer in existence) was sparse because she was not there very long (she was actually there for nine months in 1943), but implies that he was given access to the remaining records, which would have been in violation of several state and federal laws regarding patient privacy. Arnold also reproduces a doctor’s quote (“She now seems fully recovered”), without providing the context that it was actually part of an April 1943 news report that Frances was about to be released from the private sanitarium. Unfortunately, she must have suffered a relapse (as was to happen repeatedly) and ultimately did not get out until September 1943, and then only after she had run away and Lillian legally intervened.

Frances and Lillian on the Paramount lot, 1936.

FRATER AND THE AMERICAN VIGILANTES

Arnold paints a sinister picture of Judge Frater, who signed Frances’ original commitment order in Washington, and the right-wing group Arnold claims the Judge was a member of. Exhaustive archival research has failed to turn up anything other than a few passing references to a group (evidently a militia) called The American Vigilantes of Washington. No record of any connection with Judge Frater has been found. Arnold provides no supporting documentation whatsoever for his claims that Frater orchestrated much of what went on behind the scenes in Frances’ commitment. Aside from Frater signing the 1944 commitment order, the public record provides no such information.

LILLIAN’S GUARDIANSHIP

Completely glossed over in Arnold’s account (perhaps because it caused problems with his hypothesis) is the fact, amply documented in archival court records, that Lillian Farmer was appointed legal guardian of Frances during Frances’ first commitment at Western State (she had in fact first fought for, and won, guardianship after Frances escaped from the private sanitarium in California in 1943). Lillian remained Frances’ guardian until Frances was formally discharged on March 25, 1951 (one year after her parole on March 25, 1950). Arnold’s assertion that the many therapies (including lobotomy) that Frances allegedly endured ignores the fact that Lillian would have had to approve them. The Farmers have consistently maintained that Lillian (and Ernest) Farmer were very directly involved in approving any and all therapies used on Frances, and that lobotomy was specifically rejected as even a possibility. Arnold does mention Lillian’s guardianship with respect to the 1945 recommitment, but he has the details and timing incorrect, as the public record clearly shows.

LILLIAN’S ATTITUDE TOWARD FRANCES’ CAREER

Arnold excoriates Lillian for insisting that Frances attempt to resume her career despite Frances’ ongoing emotional turmoil. In fact Lillian is directly quoted several times defending Frances’ decisions concerning her career. As early as 1944, when Frances had been released from Western State for the first time, Lillian stated to the Seattle press, “[Frances] is going to have a rest with my sister in Nevada before she goes back to work…I don’t want her to try to do too much at first.” When Frances herself was interviewed in July 1944 with Lillian present, press accounts state that Frances “shushed” Lillian when Lillian said that Frances had thought about pursuing a nursing career instead of going back into show business. In these contemporary first-hand interviews, Frances followed up Lillian’s comment by quickly stating that she intended to make a show business comeback as soon as possible.

A year later in 1945, after Frances’ second release from Western State, and when comeback talk was still quite active (Frances was still receiving offers for film work), Lillian is first quoted as saying “Frances will make her announcement when she is ready” regarding any comeback attempt; and later in 1945, when Frances’ emotions were still in upheaval, Lillian is quoted as saying “Frances will make no attempt at a movie comeback.” In 1946, nationally syndicated columnist Jimmie Fidler (who regularly reported about Frances’ troubles) quoted a letter he received from Lillian, in which she stated: “[Frances] is handicapped by the fact that she was a stage and screen star. That is the one thing she wants to forget and wants others to forget. It is a strain on her emotional stability when absolute strangers walk up to her and ask her for her autograph, or try to engage her in conversation about her career or illness.” These hardly seem to be comments from a woman hell-bent on insisting her daughter resume her career at any cost.

Most interestingly, during Frances’ numerous 1957-58 comeback interviews, she repeatedly told interviewers that part of the stress leading to her breakdown was due to her family’s wishes that she quit show business, when she herself did not want to! Among other accounts, she is quoted in a nationally syndicated article by Lloyd Shearer which ran on June 9, 1957 in Sunday supplements as saying her breakdown was caused by “an emotional letdown after my divorce, the strain of work and the problems brought on by my family’s wish that I quit Hollywood” (emphasis mine). Interestingly, the article also profiled Gene Tierney, Frances’ co-star in Son of Fury and another Hollywood legend who battled mental illness for years.

The May 4, 1958 American Weekly article cited above also contains an explicit reference that Lillian wanted Frances to quit show business, which Frances was loathe to do.

The 1948 gate at Western State Hospital, built when Frances was a patient there.

ORDERLIES AND SERVICEMEN AT WESTERN STATE

Arnold states that the orderlies at Western State were inmates (presumably male) and acted as pimps for marauding Ft. Lewis servicemen. Nurses who actually worked at Western State during Frances’ committals there have stated clearly in interviews that the hospital never mixed the sexes (with the exception of occasional social gatherings for holiday parties, etc.), either in terms of patients’ living wards or those caring for them. In other words, only female nurses and orderlies cared for female patients, and any ward where Frances was placed would have only had other female patients. The nurses are also on record stating that no “truckloads of soldiers” were ever at Western State for illicit sex, with Frances or with anyone else; one would have to believe that a female nurse or attendant would have been willing to “pimp” her patients to believe Arnold’s account. Arnold also provides no substantiation for his claim that orderlies/attendants were “trustee inmates.” There were well-publicized complaints by affected Unions when some conscientious objectors, part of the Civilian Public Service program, were volunteered to be attendants at less money than their Union counterparts. One would think that any hire of “trustee inmates” would have raised the same outcry, but there is absolutely no mention of inmates being used in contemporary press accounts.

[Years ago I also quizzed my late father, a U.S. Army General who was Sr. Officer at Ft. Lewis for many years (there was a building there named after him), and he told me it would have been logistically next to impossible for anyone (let alone “truckloads of soldiers”) to secretly make it onto Western State grounds, and then into the facility itself and ultimately into a locked and guarded ward. This is merely anecdotal and offered only as a personal aside.]

THE 1945 SANITY HEARING

Arnold claims the hearing was held by King County Hospital Superintendent A. J. Hockett, who ordered her recommitment. Commitment is a judicial procedure and only a judge can order a commitment. A May 22, 1945 Seattle newspaper article clearly states that Superior Court Judge Hugh C. Todd held the hearing.

1946 PAROLE

Arnold dismissively states that after Frances was recommitted in May 1945, Lillian “saw to it that she stayed there for the next five years.” Archival hospital records show that Frances was paroled for about two months in early 1946, from March 3 to April 30, formally to her father, but at the West Seattle address where Lillian lived. This previously undisclosed material clearly shows that the Farmers continued to try to allow Frances to function outside of the hospital. (There is an October 1945 news article indicating Frances’ release was imminent and that she had taken a job as a typist. What may have happened is that Western State and Lillian decided to keep the ultimate release quiet so as not to add to Frances’ pressures).

DRUG THERAPIES

Arnold alleges that by 1947 Frances was “integrated” into a drug program, including “most likely LSD.” The first clinical use of LSD in the United States was in Boston in 1949. Records clearly show that the only “experimental” drug used during Frances’ stay was a neurological agent designed as an anti-seizure medication; it was not a psychiatric drug. In fact, the first anti-psychotic drug, chlorpromazine (Thorazine), was not introduced anywhere in even a testing environment until 1952, two years after Frances left Western State. Western State itself did not receive the drug until 1954, four years after Frances’ exit. (It’s interesting to note that Scientology’s purported “watchdog” group the Citizens’ Commission on Human Rights ups the “drug” ante in their frequent use of Frances’ story as part of their infamous anti-psychiatry campaigns, insisting that she was used as a guinea pig for a whole retinue of psychotropic drugs, some of which weren’t developed until a decade after her release from Western State. They also make a series of other unattributed allegations about Frances’ mistreatment, following Arnold’s lead of not providing sources or documentary evidence to support their claims. For more information on the Scientology connection to misinformation about Frances, see below).

ELECTROSHOCK PROCEDURES

Arnold goes into salacious detail about the seizures caused by electroshock, stating that patients were not given sedatives or muscle relaxants before treatment. Records clearly show that small doses of curare were routinely used as a muscle relaxant for all convulsive therapies (i.e., insulin or electroshock).

FRANCES’ THERAPIES

Though some hospital records are not complete (notably hydrotherapy), existing data show that Frances underwent only one series of electroshock (for about three months in 1945, shortly after her recommitment), once more in direct contradiction to Arnold’s assertions (who claims she first underwent extensive electroshock in 1944 and spent the next year recovering behaviorally from the experience). There is no existing data showing Frances underwent any insulin or hydrotheraphy treatments during her stay at Western State.

DIRT FLOORS AND FIRE HOSES

In one of the most over-the-top descriptions in his book, Arnold excoriates the living conditions at Western State, which indeed were far from excellent (as evidenced by numerous press accounts which documented the hellish conditions at the institution). However, exhaustive historical data regarding both the physical condition of Western State and its protocols for patient care show no patients were kept in any area with dirt floors (indeed no supporting documentation for dirt floors anywhere in the facility could be found), and no fire hoses were ever used to bathe patients.

1946 ELECTROSHOCK TREATMENTS

In one of the few passages in his book where he actually names a source (Nurse Nancy Lilly), Arnold again alleges Farmer underwent routine, extensive electroshock when she would refuse to work. The hospital records show no treatments whatsoever for Frances during 1946 (on top of which she was paroled for some of that time, as discussed above). Though certainly not definitive, no mention of a Nurse Lilly was found in any of the records examined for this article.

THE FREEMAN VISITS TO WESTERN STATE

In the most sensational segment of his book, Arnold claims that the infamous Dr. Walter Freeman lobotomized Frances during his “second visit” to Western State in late 1948. Western State preserved all of its information about Freeman’s visits, including copious correspondence between Freeman and Western State’s Superintendent Keller. In actual fact, Freeman really visited Western State four times in the 40s, in 1941 (for a conference, before he began using the transorbital technique), 1947, 1948 and 1949. Freeman performed transorbital lobotomies at Western State on three dates during Frances’ commitment there: August 19, 1947, October 15, 1948 and July 7, 1949. (He would perform seven more on July 19, 1951, several months after Frances had received her formal discharge). Archival data clearly show all of Freeman’s surgical subjects, and Frances was not among them. Indeed, Frances was not operated on by any doctor for any reason whatsoever during her stay at Western State.

Additionally, Dr. Charles H. Jones, psychiatric resident at Western State who was trained in the transorbital procedure and who assisted Dr. Freeman in some of his Western State surgeries, wrote in a 1987 letter to the King County Medical Association that Farmer was not lobotomized. Interestingly, Jones stated he had been contacted by Arnold during Arnold’s research for his book, and Jones maintained he told Arnold no lobotomy was performed on Farmer. Finally, published interviews with surgery and lobotomy ward nurses who worked at Western State during Frances’ commitment also are unanimous in their refutation of Arnold’s claim about the lobotomy (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, January 26, 1983, among other sources).

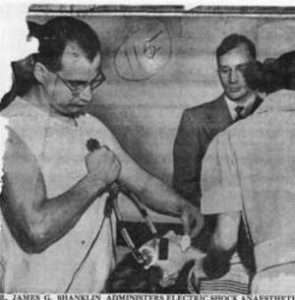

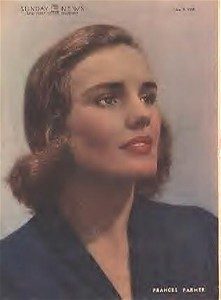

The infamous photo of Freeman’s 1949 visit to Western State Hospital.

RELATED LOBOTOMY INFORMATION

Though not all of this is explicitly mentioned in Arnold’s book, a couple of “urban legends” have grown out of Arnold’s account, notably that the picture of Freeman operating on a patient (included in Arnold’s book) is actually a picture of Freeman with Frances (Freeman’s son makes this claim in David Shutts’ 1982 book Lobotomy: Resort to the Knife as well as the E! Mysteries and Scandals episode about Frances, but it is interesting to note that Arnold makes no such claim in his book where one would logically expect him to). This is the photo in question==>:

There are several facts to consider regarding this claim. First of all, Arnold claims Freeman lobotomized Frances “privately”, away from any spectators. Archival material shows very clearly that Freeman did all of his Western State operations with many spectators and assisting physicians in attendance, not to mention routine press coverage (as patently proven by the photo itself).

Indeed, Freeman was aggressively marketing the transorbital procedure to state institutions nationwide, and was utilizing Western State and Western State’s Superintendent Keller as marketing tools during this campaign, as is emphasized in copious correspondence between Keller, Freeman and several other state institutions, as well as numerous press accounts in the Seattle press from 1947-49. Therefore, Freeman was amassing case histories and supporting data on all of the transorbital patients at Western State, whether or not Freeman himself did the operations (though the original 13 patients whom Freeman personally lobotomized during his August 1947 visit were the subject of particular interest). In other words, Freeman wanted publicity (and got it–all three of his 1947-49 visits were well-covered by the press). He would never have secretly operated on anyone, let alone someone of Farmer’s stature. What better advertising gimmick could Freeman have had than “curing” a famous movie star with his controversial operation?

The second, unattributed photo showing the same patient being electroshocked before the lobotomy. The patient is obviously not Frances Farmer. (This photo is reproduced from the actual newspaper account found in the July 8, 1949 Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Arnold’s reproduction of the picture does not divulge that it is the same patient being shown lobotomized in the other, more infamous, photo)

More to the point, however, with regard to the photo itself: there are actually several shots of this same patient, including one taken after the operation, and it is clearly not Frances. (It should be noted that this operation was actually part of the July 1949 visit, again refuting both Arnold’s claim that Frances was lobotomized in 1948 and his own caption for the photo in his book, which states it is 1948. This visit was evidently part of a “photo op” with the Seattle papers, for accounts of this wave of operations were published, including with this photo). The record clearly proves who the patient was. Freeman only personally performed three lobotomies that day (two of them women), while other Western State physicians did the rest with Freeman providing assistance. The patient’s name will not be reprinted here out of respect for privacy concerns.

Though it is not properly attributed, one other photo from this same series with the same patient is actually printed on the previous page of the hardcover version of Shadowland, showing Western State physician James Shanklin administering electroshock to the woman before Freeman performs the lobotomy. Though her eyes are masked in the photo, the woman is clearly not Farmer. (Shanklin was one of the other doctors trained in the transorbital technique, frequently assisting Freeman, and who also personally performed many of the transorbitals at Western State).

A close-up view of the patient featured in the 1949 photo series. Other photos of the procedure were published, including one of Freeman interviewing the subject after she had awakened post-lobotomy.

On a slightly tangential issue, but one which is germane to Arnold’s whole conspiracy theory, is the fact that correspondence between Keller, Freeman and other institutions show a marked concern for the hugely disparate outcomes of the transorbital lobotomies: some patients would literally be sent home within days of having the procedure, others would become walking vegetables. This is in complete contrast to the depictions of Keller and especially Freeman in Arnold’s book. (It should be noted that Freeman was definitely more interested in highlighting the successes than the failures, as is to be expected).

On another related side issue, Freeman himself developed stringent criteria for the patients he felt would most benefit from the transorbital procedure, which is also amply demonstrated in the correspondence with Keller as well as the press coverage. The very first of these criteria is that there should be less than six months to a year since the onset of symptoms of mental illness in any patient chosen to receive the operation. Freeman felt quite strongly that the transorbital lobotomy helped cure only the fixation aspect of psychosis, not necessarily the psychosis itself; therefore, nipping it in the bud was paramount before the fixation really had a chance to take hold. (As early as 1936, when Freeman was with Watts still performing the full prefrontal lobotomies, he is quoted in the November 30 issue of Time on this very subject: “We have not removed the idea [note: i.e., the psychosis/neurosis itself] by this operation. The idea is still there, but it has no emotional drive. I think we have drawn the string, as it were, of the psychosis or neurosis.”) Over and over Freeman, in both correspondence and press interviews, stresses that the onset of psychosis must be recent, and that most of the failures of transorbitals up to that point were due to the fact that those patients’ symptoms had been of longer duration. At the time of Freeman’s first wave of operations in 1947, Frances would have had over four years’ of a “manifest psychosis” and would not have been deemed a proper subject for the procedure. (It should be noted that a number of longer term patients did have the transorbital procedure, though usually as a trial step toward a full pre-frontal lobotomy).

The June, 7, 1948 issue of Newsweek (among many other sources, including the May 29, 1948 Science Newsletter) states this explicitly in its article about Freeman and transorbital lobotomy: “Best results are had with patients who have been ill less than a year….In patients who have been ill for more than a year, Dr. Freeman thinks transorbital lobotomy should be looked upon as a test, not as a last resort. If the patient improves, but the improvement does not last, then he thinks the standard lobotomy operation should be used.”

The troubling aspect to all of this is the regular use of lobotomies during the 40s and 50s at Western State (and indeed at virtually every state institution nationwide), a fact about which they actually seem to be proud in several press releases and formal papers, again belying Arnold’s assertions that these operations were somehow shrouded in secrecy. However disturbing these surgeries may seem to us now, the record is clear that Frances Farmer was not among the hundreds at Western State who were lobotomized.

OTHER FREEMAN URBAN LEGENDS

Again though not explicitly mentioned in Arnold’s book, a couple of other urban legends have arisen since Arnold made the lobotomy claim, notably that Freeman himself bragged about having lobotomized Frances, and that he had a photo of the operation. As biographer Jack El-Hai reported in his definitive portrait of Freeman, The Lobotomist, the truth is there is absolutely no public record of Freeman ever mentioning Frances in any way whatsoever. This includes not only his own books, but also his voluminous private patient records, which he kept with almost obsessive zeal. This would mean that Freeman, a man many have described as an egomaniac and almost compulsive publicity seeker, would inexplicably have not mentioned Frances as a patient of his, when she, along with Rosemary Kennedy, would easily have been one of his most “illustrious” subjects. This lack of mention seems even more incomprehensible when one considers the fact that Frances, unlike the unfortunate Rosemary, became at least marginally functional and went on to resume her film, theater and television work with considerable success. Wouldn’t Freeman have wanted to point to Frances as an example of what his procedure could achieve? (Freeman biographer Jack El-Hai did find one reference to Frances in some private correspondence from one of Freeman’s patients who evidently was obsessed with her, and that is the only time she is mentioned in any of Freeman’s archives).

One would assume the photo in question is the same one shown above, which Freeman’s son insists is of Frances, which is neither of Frances nor was taken when Arnold claims Frances was operated on (see entry above). Freeman’s son went on to insist that Frances’ records “disappeared” from Western State, but that’s simply not the case, as the data included in this article clearly show.

OTHER FREEMAN ERRORS

Arnold states that Freeman lobotomized 13 women in a row during the 1947 series. The record shows eight women and five men underwent the procedure that day. Extensive case histories on these original 13 were developed as part of Freeman’s marketing of the procedure. (Freeman personally lobotomized three women on October 15, 1948, while Jones with Shanklin assisting lobotomized one other woman and Shanklin with Jones assisting lobotomized one man, for a total of five. A total of nine patients, eight women and one man, were operated on on July 7, 1949, with Freeman acting as primary surgeon on three).

Arnold also alleges Freeman claimed that the transorbital procedure was a “fix-all” for a laundry list of ailments, including (according to Arnold) homosexuality and masturbation. As mentioned above, Freeman actually seemed intent on limiting expectations for what the transorbitals could achieve. No record has been found of Freeman espousing the transorbital procedure as a “cure” for the list Arnold provides. (It should be noted that some transorbital patients did suffer from what was termed “sexual perversion” or “deviancy,” but records indicate this was more pathological behavior).

THE FARMERS’ CONTEMPORARY RESPONSES

Again ignored in all of the sensational and unsupported conjecture of Arnold’s version of events is the fact that Lillian Farmer maintained guardianship of Frances and that the Farmers, including Frances’ attorney father and physician Uncle, were in regular, steady contact with Western State throughout Frances’ institutionalizations. As Edith Farmer Elliot reports in her book, Western State officials evidently did at least mention lobotomy as an option, but the Farmers rejected it firmly, seeing it (perhaps presciently) as a “guinea pig” treatment. In fact, Frances’ father threatened legal action if any treatment, let alone one as radical as lobotomy, was initiated without the Farmers’ prior approval.

1949 “RESPONSES”

Arnold again alludes to the fact that he was given access to Frances’ private medical records from Western State and that they state she miraculously began responding to treatments in late 1948 or early 1949. Farmer family members who have had access to Frances’ records say no such statements are made. Additionally, Western State has never released private patient records to anyone other than family (and sometimes not even to them). Arnold does at least hedge his hypothesis by stating that the lobotomy might have taken place “without permission,” but again, it not only would have been career suicide for Freeman to do this, it would have been totally uncharacteristic, as evidenced by Freeman’s desire for press. Both the 1948 visit, which is when Arnold claims Frances’ lobotomy was performed, and the 1949 visit, which is when the photo was taken, were covered by numerous reporters and photographers who would have obviously jumped at the opportunity to report that the famous actress had had the Freeman procedure. Finally, if indeed Frances “miraculously” started responding supposedly post-lobotomy in 1948, why was she kept institutionalized until March 1950?

1950 PAROLE

Arnold misstates the date on which Frances received her final parole (parole refers to her physical release from the hospital; discharge, which occurred one year later,is when she was formally dismissed as a parolee). The parole was actually March 25, 1950.

1950-53

Arnold again goes into minute detail about Frances’ everyday life and behavior without providing substantiation or sources. Even so, there are several factual errors in this section, including stating that 1953 was two years after Frances’ release (she was paroled in 1950, formally discharged in 1951), and that Wes insisted that Frances get a job. Ruth Farmer states clearly in tape recordings that it was Frances herself who volunteered to go to work when the family’s finances were in trouble.

Another, lesser seen shot from the 1954 national news coverage of Frances’ marriage to Alfred Lobley.

1954 AND EUREKA

There are several errors of fact in Arnold’s account of Frances’ brief marriage to Seattle city worker Alfred Lobley and her subsequent move to Eureka. Frances stayed in the marriage for seven months, not the six reported by Arnold. Arnold also states that Frances “gathered together about 75 dollars” to get her out of Seattle. I am personally in possession of a loan document Frances signed in November, 1954, for $250.00, for which she provided several pieces of jewelry as collateral. Sadly, Frances acquired this loan right before Thanksgiving, 1954, which means she moved, alone, to Eureka during the beginning of the holiday season that year. Interestingly, Edith Farmer Elliot reprints a letter from Lobley where he states he hadn’t seen Frances since late October, 1954. The loan document was signed in Seattle, which means that Frances must have “hidden out” in the city, away from Lobley, before she got sufficient funds to travel to Eureka. Finally, Arnold claims that Frances “utterly vanished for three and a half years.” Frances moved to Eureka in late 1954, and was “discovered” again in early 1957 working in San Francisco. That means her time in relative anonymity was a little over two years.

Frances outside of Television City circa 1958.

ED SULLIVAN

Arnold claims that Sullivan made “a long and patronizing speech” about “this pathetic woman” during Frances’ first appearance on his show. Sullivan is actually excited (for Sullivan) and supportive of Frances during her first appearance on his show. Both Farmer episodes still exist and are maintained by the Sullivan Estate. His pre-show introduction is short and hardly patronizing: “Here, making her comeback to show business on our stage, is movie star Frances Farmer.” Later, in formally introducing Frances, Ed states: “Tonight, ladies and gentlemen, we’re very thrilled on our show because returning to show business, she picked our stage. Here’s the girl who, in Come and Get It, some years back, the movie star sang a song written by Stephen Foster [note: the song actually was not written by Foster]. The song this year came out as Elvis Presley’s “Love Me Tender.” Here is Frances Farmer, so let’s give her a very affectionate greeting, won’t you?” Those are the complete introductory comments of Ed Sullivan taken verbatim from the episode. Ed makes one more brief comment after Frances’ song, indicating he had booked her exclusively and that she would be returning soon, which she did in October 1957. Sullivan’s introduction on that second episode is similarly brief and to the point.

THIS IS YOUR LIFE

Arnold claims Frances “barely uttered a word,” was “catatonic,” and responded to questions with a “blank stare.” Nothing could be further from the truth. The episode, while emotionally wrenching due to Ralph Edwards’ smarminess, shows Frances in complete control of her faculties, responding at length, and with great intelligence, to all questions put to her, sometimes seeming to be on the verge of tears or suppressing rage at the indignity of being asked such crude questions. There are also several flashes of the infamous Farmer temperament throughout the episode, notably Frances’ curt retorts that “I didn’t think then that I was sick and I still don’t” and “If you’re treated like a patient, you’re apt to act like one” as well as her dubious reaction (seen only in the original unedited version) after being told brother Wes couldn’t attend due to military obligations.

1958 TV APPEARANCES

Among Frances’ TV appearances, Arnold lists a Lloyd Nolan series called Treasury Agent. While Nolan did play a treasury agent in the series, it was actually called Special Agent 7.

Frances in Tongues of Angels, a moving live 1958 Studio One episode which survives on kinescope and presents one of Frances’ most compelling performances.

PARTY CRASHERS

Arnold describes Frances as “burned out” and not “credible.” Her performance in this movie is easily one of the best things about it, refined, understated and compassionate. He also gives no substantiating evidence for his statements that she missed cues and was consistently drunk on-set. During this same period, Frances was appearing regularly in stock and also live television dramas. Her theater reviews are uniformly positive, with no mention of drunkenness or missed cues. Additionally, some of the live television still survives on kinescopes, and they show Frances missing no cues and clearly completely in control of her faculties and her performances.

Frances interviewing Miss Indiana State Fair Queen during an insert for Frances Farmer Presents.

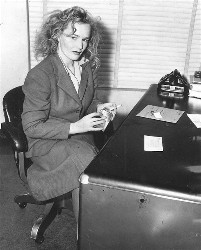

FRANCES FARMER PRESENTS

Arnold describes Frances during this period as “distant” and “never quite in control.” Videotapes of her show reveal a warm and congenial hostess, laughing and interacting beautifully with her on-air guests. Her interviews with Purdue students, made during Frances’ run there in The Sea Gull, show what a supportive mentor she was to these young adults just starting to learn their craft. Arnold also claims that Frances’ television duties included commercials. Frances’ WFBM contract specifically stated she would never appear in commercials, and usually Indianapolis personality Carolyn Churchman would do the commercials during Frances’ show.

1964 RATINGS

Arnold states that by early 1964 ratings for Frances Farmer Presents had “drastically fallen off.” Frances’ tv show remained the number one show in its time period from its debut in 1958 until the day it left the air. Frances’ 1964 ratings actually hit new highs due to the publicity surrounding her spring appearance on the Today Show. In fact, when WFBM and Frances parted ways, the station manager at a competing station hoped to hire Frances himself to improve his station’s ratings, but Frances did not follow through after an initial phone contact.

THE TODAY SHOW

Arnold misidentifies the guest host of the show that day as John Daly, best known as the host of What’s My Line? on CBS. A CBS star would have never been permitted to “moonlight” on an NBC broadcast. Contemporary TV Guides show that the guest host that day (April 21, 1964) was in actuality James Daly, father of Tyne, and later co-star of the 1970s series Medical Center.

THE “FICTIONALIZATION” OF SHADOWLAND

Many people interested in Frances’ story and how it has been disseminated over the years are aware that Arnold ended up suing Brooksfilms, the producers of the Jessica Lange feature film Frances, claiming (as is obvious, actually) that the film was based on his book. What is less widely known, however, is that the basis of Arnold’s claim against Brooksfilms is that Arnold alleged that the book was not entirely based on public record fact (which would have negated his claim to exclusive authorship rights in the lawsuit), but that it was “fictionalized” (this is Arnold’s own term, from the court records). This “fictionalization” is specifically inclusive of the supposed Farmer lobotomy, as is mentioned in the Judge’s decision against Arnold, a decision in which the Judge quite pointedly takes Arnold to task for writing and marketing his book as nonfiction, then claiming afterward that it really wasn’t. From the Judge’s decision denying Arnold’s claim of copyright infringement:

“Shadowland was presented to the public as a non-fiction work. Any reader of the book would have concluded that the book presented a true account of the life of Frances Farmer, the result of Arnold’s investigative journalism. The book itself purports to be a true story. It was released to the public as a non-fiction work. All of the promotional materials and reviews of the book treated it as non-fiction. Plaintiffs [note: i.e., Arnold and co-plaintiff Noel Marshall] at no point prior to this litigation ever suggested publicly that the book was in part ‘fictionalized.’ This is not to say that Shadowland is indeed a truthful account of the life of Frances Farmer. The evidence introduced at trial established that portions of the book were fabricated by Arnold from whole cloth despite the subsequent release of the book as non-fiction.”

This is perhaps the most telling argument for any reader objectively assessing Arnold’s claims. (With regard to the film adaptation, it’s interesting to note that Arnold in his acknowledgements thanks Marie Yates, who according to a People magazine article about the lawsuit was Arnold’s original literary agent and who later became co-producer of the feature film Frances, and thereby a co-defendant in the lawsuit. This would suggest that Yates and Arnold had a film deal in the works before the release of the book, as is indeed alluded to in the People magazine article).

THE WILL THERE REALLY BE A MORNING? FACTOR

As indicated above, Arnold frequently repeats information evidently gleaned from Farmer’s supposed autobiography while at the same time lamenting (correctly) its manifold errors. Unfortunately, according to several members of the Farmer family Will There Really Be a Morning? not only is as rife with errors as Arnold’s book, it is also as sensationalized. Unlike Arnold, however, Morning’s “real” author, Frances’ late-in-life friend Jeanira Ratcliffe, was reportedly quite forthcoming (in private, at least) about how she had sensationalized Frances’ “memoirs” in order to facilitate a movie sale. Beyond the perceived sensationalism, however, are undeniable errors of fact that Frances herself would never have made. David Farmer points out that Morning misstates the names of Frances’ grandparents, for example, and many other errors – names of films, names of plays, names of co-workers – pop up with great regularity in the book. Despite these errors, Frances’ former friend Ida Lupino was close to optioning Morning for filming (it was later adapted as a tv movie with Susie Blakely as Farmer) before her (Lupino’s) death. Frances did have plans to write her own autobiography (she was a stunningly gifted writer, as is evidenced not only by her adolescent writings, including the infamous God Dies essay, but also her mature poems, which are as deep and imagistic as Anne Sexton’s) and granted several interviews to Lois Kibbee during this process. Kibbee’s preliminary work on the autobiography (including actual quotes from Farmer) is referenced in Patrick Agan’s Decline and Fall of the Love Goddesses, and remains, along with the 1958 American Weekly series Frances co-wrote, the only unfiltered example of what Frances’ actual autobiography might have been like. Kibbee also recounted her interviews with Frances in a revealing series of recordings which Patrick Agan provided to me some years ago. For those who can get a copy, it’s fascinating to read Frances’ 1958 version of events in American Weekly, as telescoped as they are. Several salient pieces of information are in direct contrast to Ratcliffe’s recasting of events in Morning.

CONCLUSIONS

William Arnold was the first person to allege Frances Farmer was lobotomized. He provides absolutely no supporting evidence, either documentary or otherwise, in his book. Conversely, many people intimately connected with the case are on record, using their names, saying no lobotomy ever was performed on Farmer. The Farmer family has always insisted no operation took place. Nurses who were there at the time insisted no operation took place. Definitive archival records clearly show that Frances was not operated on. Western State was excited about their lobotomy program and certainly would not have kept an operation on Farmer secret for any reason; Keller and Freeman were both eagerly seeking press coverage of the lobotomies, and were in fact successful in garnering copious press for the program at Western State.

What could William Arnold’s motives have been for so severely distorting the record of Frances’ unfortunate troubles? Edith Farmer Elliot, among others, maintained that Arnold was a Scientologist, intent on furthering Scientology’s late 70s push to have psychiatry discredited, though Arnold himself has reportedly stated he is not affiliated with the group. (As recently as 2004, Scientologist Tom Cruise was on record as saying “Psychiatry is an utter waste of time and should be outlawed”). In his acknowledgements, Arnold himself thanks at least two Scientologists or Scientology groups, including the Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR) and Heber Jentzsch. Indeed, in the People magazine article referenced above, it is explicitly stated that Arnold and Yates met through the Scientologist publication Freedom, and to this day the CCHR’s publications and website continue to quote liberally from Arnold and utilize Frances’ supposed mistreatment and ultimate lobotomy as the prime example of what the “horrors of psychiatry” can do.

Why Arnold chose Frances to be his “poster child” is unknown, other than that she provided an obviously riveting “hook”; certainly his quite laudable thesis regarding psychiatric abuses could have been just as well served by the actual facts, without the “fictionalizing” Arnold added. As is sadly described in archival records, between July 23, 1942 and June 12, 1953, 252 pre-frontal and transorbital lobotomies were performed at Western State. These poor souls suffered no less by reason of the fact that Frances was not among their ranks.

Supporters of the belief that Frances never underwent a lobotomy have long labored under the burden of having to prove a negative. With the overwhelming weight of this clear documentary evidence, the burden of proof now shifts to those who insist the operation took place, yet who fail to provide documentary evidence of any kind.

Frances Farmer was undoubtedly a deeply troubled woman who suffered greatly in her life. The relatively primitive conditions of the state institution system, as well as the equally primitive therapies used in those days, no doubt exacerbated rather than helped her condition, as Frances herself stated more than once. However, sensationalizing and “fictionalizing” what this brave woman went through not only does a disservice to her memory, marginalizing her very real tribulations, it also prevents us from objectively understanding Frances’ trials in their proper historical context. A clear-headed, fact-based approach is the only way we can assure that the mistakes of the past are not repeated and that Frances’ valiant struggle to maintain mental and emotional equilibrium stands as an inspiring example for those similarly afflicted.

Frances Farmer was undoubtedly a deeply troubled woman who suffered greatly in her life. The relatively primitive conditions of the state institution system, as well as the equally primitive therapies used in those days, no doubt exacerbated rather than helped her condition, as Frances herself stated more than once. However, sensationalizing and “fictionalizing” what this brave woman went through not only does a disservice to her memory, marginalizing her very real tribulations, it also prevents us from objectively understanding Frances’ trials in their proper historical context. A clear-headed, fact-based approach is the only way we can assure that the mistakes of the past are not repeated and that Frances’ valiant struggle to maintain mental and emotional equilibrium stands as an inspiring example for those similarly afflicted.

[The author has spent decades researching the Farmer story, and relied on archival source material for this article, including newspapers, historical documents and records released through FOIA requests, privately held records and correspondence, and relevant court and medical records. The author thanks (the late) Edith Farmer Elliot, David Farmer, Patrick Agan and Jack Randall Earles for their assistance in gathering the documentary evidence supporting this article, and to “E” for pointing the way to important information used in this research].

Responses to this article are welcome. Send Mail